Miles From Nowhere.

First, forget your modern life ….

In 1990, there was no Bluetooth, Wi-Fi, Google Maps, or Ride With GPS. The invention of mobile phones, digital photography, and even the Internet was years away. You had to carry a camera to shoot a photo, and when you were out of film, you were out of luck. Pay phones were still a thing. The expectation of instant connection to everyone you knew was science fiction.

Navigation was tricky. When you reached a new town and wanted to know where a particular store or swimming hole was, the easiest course of action was to ask another human, face to face!

People were accustomed to giving directions back then.

State maps were commonplace, but charting a route through an unfamiliar town using back roads was a byzantine task.

We lived in a murky, wonderful, analog world.

None of this was on my radar in the fall of 1989. It was just the way it was.

But now it suddenly mattered. A few weeks earlier, in a stroke of ambition/daring/naivety that still leaves me gobsmacked, Chris Hilbert, Christy Peterson, and I decided to ride bicycles from someplace in Southern California to Yellowstone, Wyoming, the following summer.

Now we just had to figure out how to do it. (We also needed to buy bikes and camping gear, but details, schmetails…)

I blame Barbara Savage. Her 1983 book, “Miles from Nowhere: A Round the World Bicycle Adventure,” was a gateway drug that burrowed so deeply into my gulliver that traces are still easy to spot today. Along with her husband, Savage rode 23,000 miles through 25 countries in two years, seemingly devising their daily routes on the fly.

That strategy wouldn’t work for us. First, we had a finite amount of time: six weeks, at most eight. Next, some planning seemed mandatory. I mean, how far was it to Yellowstone? How long would it take? What mountains/deserts/killer highways stood in our way? Where would we stay? Was food and water available?

These weren’t insignificant questions, and finding answers would take weeks.

Fortunately, I found a secret weapon in a small, brightly lit room on the second floor of the SDSU library. The Map Room housed thousands of local, county, and USGS topographical quadrangle maps, state maps, and navigation ephemera in dozens of wide, wooden cases with very shallow drawers. The king of this domain was a stooped man with a patient face who smelled faintly of dust. He answered my questions, and day by day, the route slowly took shape.

To start the trip, we’d use the best cheat code available: Tom Kirkendall and Vicky Spring’s seminal book Bicycling the Pacific Coast. This would take us to Oregon and give me insight into route planning so that each day would remain a “vacation” and not a “death march.” I mostly succeeded.

We’d skip L.A. and its traffic, starting in Lompoc at the home of Christy’s roommate. We’d follow the Kirkendall book for fifteen days as we mostly camped and rode along the California coast.

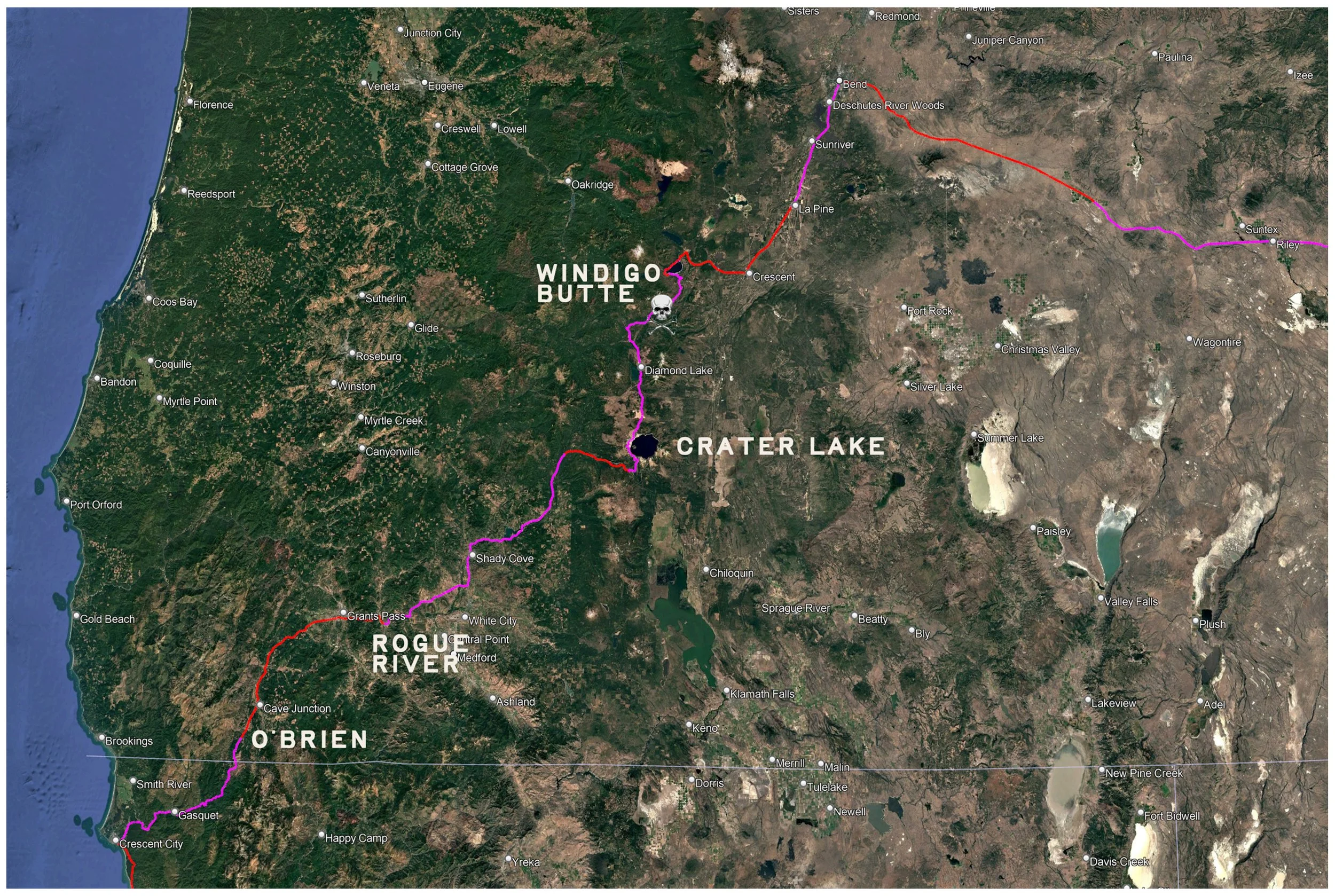

From the California/Oregon border, we’d head northeast to Christy’s cousin’s house in Grants Pass before climbing to Crater Lake.

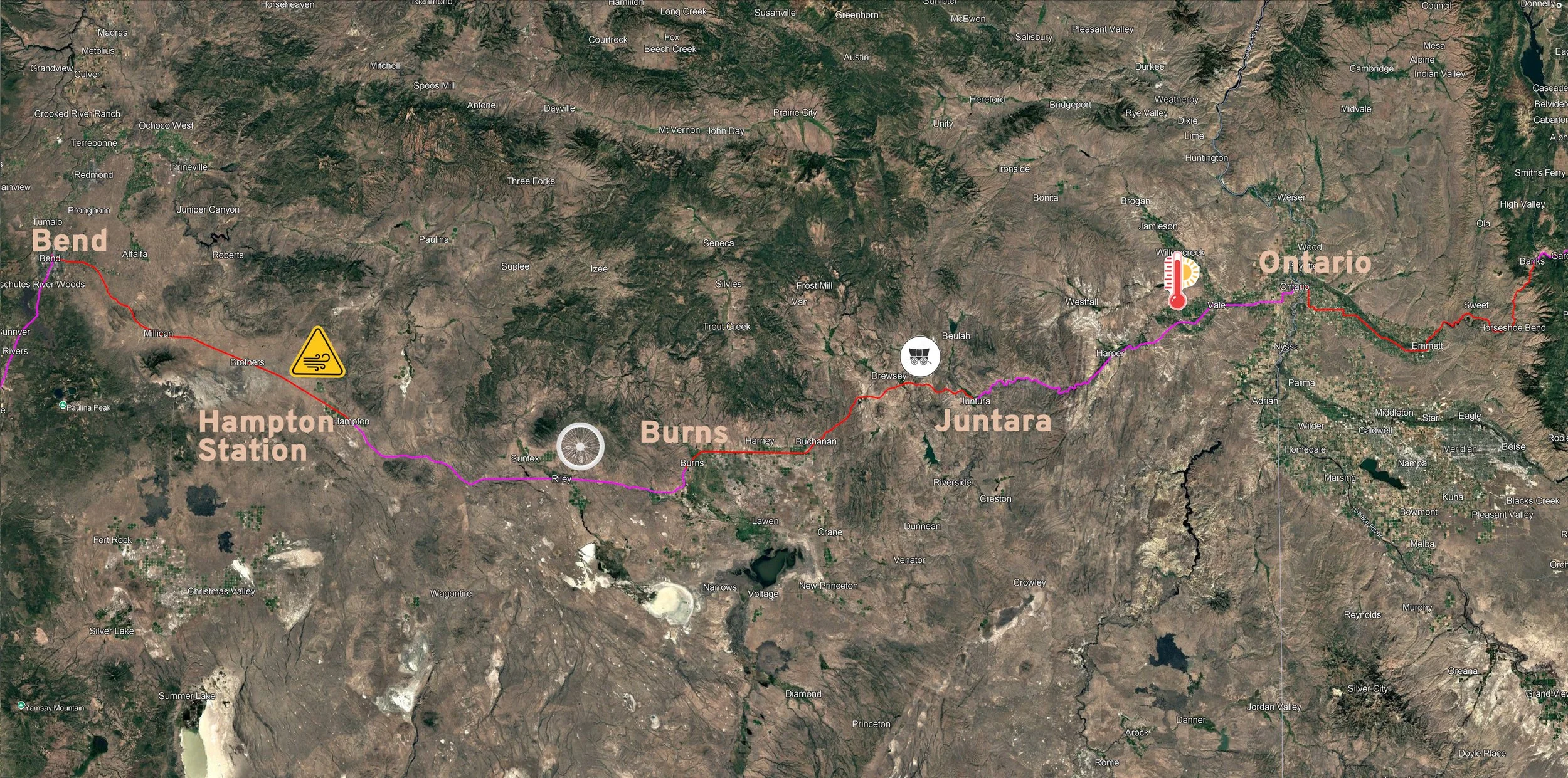

From there, we’d ride the Cascade Lakes National Scenic Byway to Bend, cut across the high deserts of Southern Oregon, and climb up and around the Sawtooth Range of Central Idaho.

We’d follow the Salmon River downstream for 120 miles before climbing over the Continental Divide at Lemhi Pass, where Sacagawea led Lewis and Clark into the unexplored west in 1805.

Some remote dirt road riding in SW Montana through the Centennial Valley would drop us off near our primary destination: Yellowstone National Park. We’d spend five days riding around the park before heading south past the Grand Tetons to the finish line in Jackson, Wyoming—44 days and about 2,000 miles from our start in Lompoc.

By Christmas, we were thinking, “This just might work.”

Countdown to Launch.

(Spring 1990) — We bought our bikes at Adams Avenue Cyclery in Normal Heights on October 5, 1989. Our route included several days on dirt roads, and the stability and ruggedness of mountain bikes seemed appealing. We chose Specialized Rockhoppers, the pared-back, less expensive version of the famous Stumpjumper, one of the first widely produced mountain bikes.

Chris and I lived in Tierrasanta then, close to Mission Trails, where we rode many afternoons that Fall. Weekends were for longer rides, braving the busy roads of Mission Valley to the beach, arriving back home sweaty and exhausted Saturday evening in time to watch Star Trek: The Next Generation. Yeah … nerds. Sue me.

We slowly worked our way through our gear shopping list, relying heavily on Christmas and birthdays for the larger items. Money was tight. Each addition was a triumph, a totemic representation of our coming adventure. Buying our North Face Bullfrog tent and then our Blue Kazoo sleeping bags were both causes for celebration.

Then, a setback: Chris backed out of the trip. Christy and I faced a brief crossroads when the trip hung in the balance, but it didn’t last long. Soon, it was all systems go again.

Of course, it wasn’t without a few bits of turbulence. Telling Christy’s folks about our plans the previous Fall had been nerve-racking, even if one of their questions (“What if you get a blister?”) later became a sarcastic rallying cry when things got tough. When I told my brother, he just shook his head and said, “What a dumbshit.”

Spring 1990 arrived, and the route continued to firm up. The paycheck from my North Shore article was perfectly timed and sorely needed. Reservations were made at the Old Faithful Inn. We called campgrounds to confirm that they offered “hiker biker” sites where reservations weren’t required, and the cost was minimal. We continued to ride, but failed to rack up much mileage.

The idea of riding for 46 days only to take a two-hour flight back home was ruled out. We’d stay on the ground for the duration. Once in Jackson, we’d drive a rental car to Salt Lake City, then jump on an Amtrak sleeper train to Fullerton ($316 for a private “roomette”).

I continued visiting the Map Room, focusing on the dirt days north of Crater Lake, over Lemhi Pass, and through Centennial Valley. Sitting in the library’s air-conditioned comfort, nothing looked too long or too steep.

Finally, school ended. Christy went up to her mom’s in Big Bear for a month, where she’d wait tables and save money. I took up residence in Leisure World, on the very short loveseat in my grandmother’s den. She was invariably awesome about having me stay with her.

A few weeks before the trip, I loaded my bike for the first time and headed south from Leisure World. It rode like a tank, the hills through Dana Point magnified in difficulty by the weight.

I reached the Camp Pendleton gates south of San Clemente and turned around, only to completely crack in Laguna Niguel. I wobbled into Oso Park, lightheaded and sweaty, and crashed out onto the grass, my world spinning. Was I dying? Would I ever stand again? I checked my bike’s odometer: 51 miles.

Of fuck, fuck, fuck. What had I gotten myself into?

The gear list.

Part One: The North Coast

Day 0: Off To Lompoc

-

Date: Saturday July 6, 1990

Miles: 212 (Car)

Total Climb/Descent: N/A

High Point / Low Point: N/A

Feet Per Mile: N/A

Route Score: 0 (Travel Day)

-

We’re jumping quite far down the road here, but on day 37 of the trip, Christy lost her left rear pannier. The last photo of it was near Red Rock Pass, so it was either lost on the descent to Henry Lake (an altogether reasonable assumption) or it was swiped once we got to Staley Spring Lodge (less likely, but something I’ve never been able to discount altogether).

Why talk about this now? Only because that pannier held seven rolls of exposed film, all our shots from Lompoc to Central Idaho. Losing those photos felt devastating then, and it still stings a bit now.

So, the photos we have from the beginning of the trip are either from Lisa and Barry, who drove us to Lompoc, or from our fellow bicycle tourers we met along the way. It’s fantastic that we have those shots, but they are a poor substitute for our own photos. A massive chunk of the trip has no photos at all.

-

Barry and Lisa drove us to the start of the tour, a rundown hotel outside of Lompoc near Vandenberg Air Force Base.

Over the past six months, Christy and her ex-roommate, Keri, had drifted apart, so starting at Keri’s house in Lompoc was no longer an option.

That was just as well. Nerves and emotions were high the day before the start of the ride, and it was nice to spend it with close friends.

Barry and Lisa even created tour t-shirts for us with “Peterson & O’Brien Summer Tour 1990” boldly emblazoned across the back, which was awesome.

-

We spent that night packing and repacking our bikes, but it all went quickly. We had the gear, the bikes, the route, and (most importantly) the enthusiasm needed. It would be a lie, however, to say that we had the confidence. That would come later, in a slow transformation that was only startling in retrospect. That night, however, the next 40 days were still a huge blank spot on the map.

Friday, July 6, 1990: A BBQ at Robyn's house the night before we left.

Packed up and ready to go. Saying goodbye to Christy's dad in Laguna Niguel.

Saturday, July 7, 1990: Packing and repacking the night before the start.

Day 1: First Miles to Pismo Beach

-

Date: Sunday, July 8, 1990

Destination: Oceano Dunes C.G., Pismo Beach (C2)

Miles: 40

Total Climb/Descent: Up 1,973 / Down -2,303

High Point / Low Point: 720 feet / 3 feet

Feet Per Mile: 49

Route Score: 53 (Moderate)

-

There’s no denying it: the bikes are heavy. We wobble out of the hotel parking lot and head up onto Highway 1, the Cabrillo Highway.

My heart is hammering, and it’s not because of the hills. But the feeling is electric.

At mile one, we make a short, steep plunge into and then out of a canyon: our first taste of how the bikes handle with speed.

Just before mile five, we reach our first navigational waypoint: a right onto Hwy 1.

A two-mile steady climb up to Hwy 135 finally settles the nerves, and we warm up and settle in.

We begin a long, easy descent through farm country near Santa Maria. The sun is out, the shoulder is broad, and we whoop with the feeling of freedom.

-

We zoom off the mesa at mile 36 on a steep descent through eucalyptus groves, with great views of Pismo Beach to our left.

It’s early afternoon—we certainly have not set a fast pace—and we stop at Central Market and load up with spaghetti, a can of green beans, Chips Ahoy cookies, and green Gatorade.

We make it to the Hiker/Biker campsite at Oceano Dunes Campground and find it full of fellow riders, who greet us warmly.

We find a place to set up our tent, still feeling a bit tentative and noobish.

It’s a welcoming bunch; some are nearing the end of their ride down the coast from Canada, and wear the clear patina of experience.

Many comment on how brave we are to be riding north, against the prevailing winds. We nod, but consider the warnings overblown, as they would turn out to be.

The most memorable person that evening is Abe, a 50-something man with a beard and pot belly, who proudly shows off his glass stein for beer drinking. It weighs a ton and seems vaguely foolish.

He’s a real character who seems to be going through a life crisis. He just recently left home and claims this isn’t a trip, but his new lifestyle. He says he’ll be riding until further notice.

-

July 8, 1990

Day One Pismo

The day had finally arrived. Barry and Lisa sent us off to a cold, cloudy morning. The adrenaline pushed us over our first hills, which was good! About 26 miles into the ride, my spirits plummeted, but then came back : )

Once inside the camp, we set up and took a little nap. We meet some interesting bikers. One guy had tons of advice about Yellowstone and everything else.

We walked over the dunes and watched the sun set into the fog bank. Then we stuffed ourselves with/ spaghetti. Yum yum. We got back, had a beer and some campfire talk with Fred & Abe (interesting), and an early bedtime @ 9:30. zzzz zzzzz

Day 2: A Full Day to San Simeon

-

Date: Monday, July 9, 1990

Destination: San Simeon Creek Campground (C2)

Miles: 54

Total Climb/Descent: Up 2,068 / Down -2,031

High Point / Low Point: 487 feet / 3 feet

Feet Per Mile: 38

Route Score: 75 (Moderate)

-

The route through Pismo and into San Luis Obispo is varied and scenic, with enough turns to keep us on our toes.

The legs are a bit tired this morning, so we amble slowly through Spyglass Ridge and Shell Beach before making a long, steady climb up to San Luis Obispo.

I’m hungry again, even though we just ate breakfast a few hours ago.

Temps are in the high 70s and there’s a gusty wind from the west, but neither is too bad.

The road west out of San Luis Obispo is busy, but the shoulders are good. It’s all just a bit uphill, however, which makes the pedaling noticeable.

The discomfort doesn’t last. Soon, we are freewheeling down into Morro Bay. After lunch, we head up the coast to Cayucos and then out along a beautiful stretch of coastline—the slightest taste of what’s in store over the next two weeks.

We head slightly inland and back up hill. None of the climbs look huge, but they are leg-sapping. The shoulder is narrower here, and the road is somewhat busy.

Cambria is bustling but charming. We get supplies at the market before riding the last 4 miles to the campground, tired and happy to be done for the day.

-

The hiker-biker site occupies a prime position near the beach at San Simeon Creek Campground.

We shower (another bonus!) and then head under the bridge that spans San Simeon Creek and end up on the beach.

It’s gray and cool—definitely not feeling like Southern California, but it’s beautiful.

The campground is crowded with cyclists from all over the world, but most of the faces are new.

We chat a bit but head to bed early, tired and a bit worried about the upcoming hills and narrow roads of Big Sur.

-

July 9, 1990

Day Two San Simeon

Well, the first day was finally behind us, and the rest of the trip ahead. Today was 54 miles (farther than I had ever ridden).

After adjusting the front brake, then the back brake, and changing my first flat tire, we made it to San Luis Obispo.

We had lunch at Taco Bell in Morro Bay (only 20 miles left).

We made it to San Simeon around 4 pm. The site was packed, and there were a ton of foreigners at the hiker-biker site.

I made it okay, but I'm exhausted, and I could barely stand up or sit down; my knees and legs were so sore.

We watched the sunset and went to bed @ 8:30.

Day 3: Into The Hills of Big Sur

-

Date: Tuesday, July 10, 1990

Destination: Kirk Creek Campground (C1)

Miles: 40.7

Total Climb/Descent: Up 2,944 / Down -2,870

High Point / Low Point: 789 feet / 9 feet

Feet Per Mile: 72

Route Score: 80 (Hard)

-

Day three greeted us with a cold fog blowing in on a stiff north wind.

Heading out of the campground was discouraging. This was a real headwind with a fog thick enough to make us feel clammy and spot up my glasses so I couldn’t see.

Two miles down the road, we spotted a place to regroup: A simple breakfast cafe in San Simeon.

This became more than a spot to wait for the weather to clear; it unlocked a secret weapon we used for the rest of the trip.

Schoolhouse Rock had spilled the beans years before, but packing in a large breakfast—French toast, side of ham, hash browns, coffee, orange juice—was precisely what our bodies needed.

A packet of instant oatmeal was convenient, but it just wasn’t enough.

So this was the first morning of many mornings when we’d ride for a few miles and then stop for a big breakfast. It did wonders for our stamina and morale.

-

With a large and excellent breakfast tucked away, we headed north.

Now, Pismo was fine, and Cayucos was top-notch, but we were heading into terrain that was world-famous for its beauty.

We knew this, but the view didn’t match the hype as we rode the 14 miles across the coastal plains to the cliffs of Big Sur. It was still foggy and chilly, and the undulating roads gave no respite.

In the Kirkendall book, this road looked dead flat until the towering climbs started north of San Carpoforo Bridge.

And, by not meeting that expectation, each small climb seemed strangely difficult.

But then something unexpected happened.

Maybe it was the French toast and ham finally hitting the bloodstream, or perhaps the clearing weather and the moderation of the wind, but the steep climb to Ragged Point seemed not that hard, maybe even … fun.

Here, plunging by a series of near-vertical hillsides down into the Pacific below, the Big Sur coastline wears its challenges like a crown. There’s no hiding from them, and they are apparent to see.

But unlike the “pecked to death by ducks” small rises of the plains below, there was a simple honesty in their difficulty which made them—if not easy—then easier to overcome.

Safely on the inside side of the road, and with traffic not too bad at all, we tackled one mile-long climb after another, gasping not just at the difficulty but at the fantastic views every hundred yards.

Yeah, no doubt about it, this was not only pretty cool, it was a lot of fun.

-

July 10, 1990

Day Three Kirk Creek

Today was our first day in the mountains of Big Sur. Getting there was almost as bad as the hills themselves. It was foggy, misty, and windy. : (

We met a guy who was trying to make it to Monterey that day. Impossible, but it lifted our spirits.

The hills weren’t as bad as I imagined. We had lunch in Gorda (a town consisting of a gas station, a cafe, and a mini mart). We called Lisa and wished her a happy birthday.

Kirk Creek was lovely, but there were no showers. We walked down the cliff and strolled along the beach.

Day 4: Camping In The Redwoods

-

Date: Wednesday, July 11, 1990

Destination: Julia Pfeiffer State Park, Big Sur (C3)

Miles: 29

Total Climb/Descent: Up 2,610 / Down -2,521

High Point / Low Point: 974 feet / 102 feet

Feet Per Mile: 89

Route Score: 51 (Moderate)

-

Packing up the tent, stuffing the sleeping bags, getting everything on the bike: these are no longer novel. They aren’t quite automatic yet, but we’re finding our groove. We are settling in and beginning to relax.

An easy day helps. Although Hwy 1 hits its true Big Sur grandeur along this stretch, the climbs no longer terrify us. It’s just too pretty for that.

-

The fairest realm of the elves remaining in Middle-earth, Lórien is an enchanted land of tall trees and beauty.

So, yeah, it’s not much of a stretch to equate Julia Pfeiffer State Park with this fantastical woodland realm.

There are the groves of towering redwoods, the soft murmur of the Big Sur River, and a secluded car-free campsite. Oh, plus showers, laundry, and a stocked store full of specialty pasta and cold beer.

That night, we even made a fire, illuminating the tall redwood trees around us in a soft glow that would make Galadriel feel at home.

-

July 11, 1990

Day Four Julia Pfeiffer Big Sur

Short day but hilly. Lunch @ Big Sur Deli/Market.

Beautiful campsite — in the middle of a redwood grove! Able to do laundry and take a hike. Spaghetti dinner & campfire.

Day 5: Otters, Sheets, and Pillows.

-

Date: Thursday, July 12, 1990

Destination: Cannery Row Inn, Monterey (H3)

Miles: 34.5

Total Climb/Descent: Up 2,370 / Down -2,539

High Point / Low Point: 583 feet / 4 feet

Feet Per Mile: 69

Route Score: 55 (Moderate)

-

fter three nights away from any big towns, we’d be heading into Monterey today.

Although the Kirkendall book guides riders to the campground at Veterans Memorial Park, we thought that was a bit out of the way from the attractions of town.

Maybe it was time to spring for a hotel room, with a bed and sheets and pillows and a shower.

First, however, we had to get there.

Leaving Julia Pfeiffer, we were immediately hit with a headwind from the northwest, which moderated only after we veered farther north at mile nine.

The coast was gorgeous from there. With the road less undulating and closer to sea level, the views were supreme. Hurricane Point was tranquil, and the sea stacks (“slee slacks”) around Castle Rock were gorgeous.

After everything we’d seen, I can’t say the famous Bixby Bridge was the highlight, but it was still fun to pedal across.

Soon, we entered the tony neighborhood of Carmel Highlands, which, even back in 1990, was full of over-the-top, to-die-for homes.

Fortunately, no deaths were necessary as we entered the bustle of Monterey, even braving a bit of the four-lane Cabrillo Highway, which looks more like a freeway than the quiet roads we had become accustomed to.

-

We decided early in the day that we’d aim for Cannery Row instead of camping.

Without much searching, we were able to find a room at The Cannery Row Inn ($82.50), smack dab in the heart of town and near the world-famous Monterey Bay Aquarium.

This was real vacation territory! We napped, visited the aquarium, had a waffle cone, went out to dinner, and then thoroughly enjoyed a night in a real bed.

-

July 12, 1990

Day Five Monterey

Nasty headwinds are leaving Big Sur. We got a hotel in Monterey at the “Cannery Row Inn.” Ahhh! Pillows, TV, and a bed!

Monterey Bay Aquarium was fascinating (Baby sea otter in the outside tidepool.

Dinner @ El Torito (Bad service).

Day 6: Bridge Out.

-

Date: Friday, July 13, 1990

Destination: New Brighton State Beach, Capitola (C2)

Miles: 54

Total Climb/Descent: Up 1,718 / Down -1,643

High Point / Low Point: 409 feet / 5 feet

Feet Per Mile: 32

Route Score: 62 (Moderate)

-

+ Slow is Fast

After a good night's sleep in a bed, I felt downright slothful at the prospect of today’s ride.

A quick jaunt up to Capitola, near Santa Cruz, the route promised to be a relatively easy 40 miles on mostly flat roads.

And all went well at first, as we passed through Seaside and Marina on quiet surface streets.

Farther north, we rode on the frontage roads of Highway 1, which looked very much like a freeway: a divided road with three lanes of traffic in each direction and large on- and off-ramps. Lots of cars and trucks, too.

So maybe it made sense when I didn’t take the onramp onto Highway 1 at Nashua Road, but instead continued straight through the quiet farm fields.

Two miles later, my mistake was apparent: Nashua Road ended at a closed bridge at Tembladero Slough.

Now, in 2025, you pull out your phone, load up Google Earth, and discover that numerous small bridges link the agricultural fields. With a bit of luck and a little stealth, you are back on track in ten minutes.

In 1990, however, all we saw was a road-closed sign, a tall fence across the mouth of the bridge, and a deep, ominous channel of water below, impossible to wade across.

So, we turned around.

I don’t recall that we discussed riding on the highway when we got back to Highway 1. It seemed so unlikely that it was the correct route.

We pedaled on, adding 12.5 miles to our route via a convoluted detour that eventually led us through the busy streets of Castroville.

We arrived at New Brighton State Beach, shattered. Not because the route was so hard, but because it was so much harder than we expected.

It took me twenty years to realize my mistake. That closed bridge was always off route. The correct course, the one the Kirkendall book described, always had us pedaling down that onramp and onto the busy freeway below.

Sometimes slowing down and paying close attention will save you time and energy—no matter how unlikely the recommended course first appears.

But that lesson eluded me on this day. Unfortunately, that wasn’t the end of our bad luck.

-

Day 6: New Brighton State Beach, Santa Cruz

***Friday The 13th***

Supposed to be an easy 40-mile day. First 20 mi excellent — no wind and flat. Had a snack at a fruit stand before getting lost. There was a bridge out, so we had a 10-mile detour. Once back on track, Sean got two flats!

Got to camp. Sean called Dellefield, and I called Dad. We ordered pizza and had it delivered to the campsite.

We were tired and had to wait for showers.

Early to bed & awakened an hour later by drunk campers with car headlights, hammering tent stakes, and laughing. They kept us up until 12:30.

Day 7: A Pretty Day Out.

-

Date: Saturday, July 14, 1990

Destination: Francis Beach C.G., Half Moon Bay State Park (C2)

Miles: 58

Total Climb/Descent: Up 2,990 / Down -3,088

High Point / Low Point: 479 feet / 7 feet

Feet Per Mile: 52

Route Score: 116 (Hard)

-

So how hard is one ride compared to another?

It’s a question I’ve tried to put a number on.

Some factors are out of your control. Rain or heavy winds can make the simplest, flattest ride feel difficult.

But generally, it boils down to distance traveled and elevation gained, with route surface and altitude layered in.

The math is:

(Mileage X (Elevation Gained / 1.5)) / 1000 = Route Rating Score

The highpoint of the route affects the divisor as follows;

Altitude Range

0 to 7000 = 1,000

7001 to 10,000 = 900

10,001 to 11,000 = 800

11,001 to 12,000 = 700

12,000 to 14,000 = 600

14,001 to 16,000 = 500

More than 16,000 = 400

Road surface is also factored in:

Dirt roads = -100 to divisor

Poor/rocky dirt roads = -200 to divisor

Technical singletrack or trail = -300 to divisor

All this gives the following range:

0 to 0 = Rest

1 to 21 = An Easy Ride

21 to 49 = Easier Than Most Rides

50 to 75 = Moderate

76 to 124 = Hard

125 to 175 = Difficult

176 to 225 = Very Difficult

225 to 600 = Extremely Difficult

600+ = BLACK <here there be monsters>

It’s all pretty arbitrary but it checks out.

For example: My hardest ride ever, according to this system, was from Grand Junction to Delta in Colorado. That route climbed 7,197 feet over Grand Mesa for 92 miles on good roads and reached a high point of 10,857 feet above sea level giving it a score of 554 (Extremely Difficult).

Based on my memory from that day in 2010, that seems about right.

The hardest ride on the 1990 tour had a route rating of 318, but we’ll have to wait a bit longer before talking about that.

-

On paper, this is the hardest day yet of our week-old tour.

But in 1990, we only knew it was going to be long and rolling, with possible headwinds.

So we started early and stopped for breakfast in Davenport at mile 20 before there was a breath of wind.

North of Santa Cruz, Highway 1 carried us past the open fields and bluffs of Wilder Ranch, with the ocean pressed close on our left.

Davenport’s old cement plant marked the last bit of town before the road quieted, rising and falling in a steady rhythm that never felt steep but never let us settle.

The highway lifted over one low ridge after another, dipping toward empty beaches and rocky coves before tilting skyward again.

Waddell Creek opened briefly toward the redwood canyons inland, then the Pigeon Point Lighthouse came into view, bright against its low headland.

Beyond it, farms and artichoke fields lined the inland side while a string of small beach turnouts slid past on the left, guiding us over those final rollers toward the first houses of Half Moon Bay.

-

Day 7: Half Moon Bay

Fifty-eight miles on five hours of sleep was not fun. We had breakfast in Davenport. Cute Place. Quite foggy in spots.

Sean almost hit a car after it pulled in front of him @ Ano Nuevo.

Took a nap once in camp. Got food at a store on the corner.

Met up with Abe and Fred again. We also met a guy from Missouri named Doug. We also met Fred’s friend Don, who came down from S.F.

Good conversation.

Day 8: Across The Golden Gate.

-

Date: Sunday, July 15, 1990

Destination: Creekside Loop Campground, Samuel P. Taylor State Park (C2)

Miles: 60

Total Climb/Descent: Up 3,348 / Down -3,246

High Point / Low Point: 723 feet / 7 feet

Feet Per Mile: 56

Route Score: 135 (Difficult)

-

Big Sur was days behind us, so imagine my surprise when reaching Devil’s Slide. (Map)

Since 2013, the steep, rocky, landslide-prone stretch south of Pedro Point has been bypassed by the Tom Lantos Tunnels.

In 1990, however, it was still a busy stretch of Hwy 1, perched precipitously above the ocean with clear signs of rockfall and road closures.

And did I mention the traffic?

The tricky bit didn’t last long, but it was enough to take my mind off the upcoming logistical nightmare navigating San Francisco would no doubt be.

But we had no idea of the fortuitous circumstance we’d encounter when we reached the city.

-

Riding in a city, any city, can be intimidating. But San Francisco is a special case.

Not only did it have fast-moving cars and a labyrinth of streets to navigate, but it also had its famous hills, plus tram lines and tunnels.

I was so concerned that I wrote a special, extended turn-by-turn breakdown back in the SDSU map room.

This cheat sheet was a beast. From Pacifica to San Francisco, then over the Golden Gate Bridge and through Mill Valley, Marin City, and Larkspur, there were nearly a hundred turns and waypoints.

All in all, it would be a huge day.

So we carefully made our way into the city, following Palmetto Avenue and Skyline Drive while gripping our bars—and gritting our teeth—a little more tightly.

But something felt different by the time we reached the San Francisco Zoo. Instead of roads full of cars, we saw a road full of bicycles, all heading exactly where we wanted to go.

We soon realized that we had stumbled into the 11th annual “Tour de San FRANCE-isco.” This yearly group ride attracted 7,500 riders in its day and followed an out-and-back course from Fisherman’s Wharf to the Zoo and back.

We jumped in with the riders, many of whom commented on our fully loaded bikes.

That made us feel pretty good already, but when we hit the hills and started passing road-bike riders, we knew our bodies had begun to adapt to the stresses we were putting them through. That offered a new level of confidence.

We chatted and laughed and followed a traffic-free route through the Richmond District and into the Presidio that on any other day would have been impossible.

It was with some degree of sadness that we parted ways at the Golden Gate Bridge, but within a hundred yards of riding out across that iconic expanse, our mood had changed to wonder, awe, and satisfaction. We had made our way to the Golden Gate!

No matter what happened from here on out, riding across this historic landmark would be an accomplishment worth remembering.

-

Day 8: Samuel P. Taylor

Great day! Easy route through San Fran —> ran smack into the Tour de San Francisco. We talked with others on the tour. It made the trip through S.F. go by quickly.

We had problems with Sean’s chain, so we got a new one in Sausalito. We had breakfast there.

Sam P. Taylor is beautiful! We met a couple from Colorado (Mark & Mary). They were so very lovely, and we had a great conversation.

Day 9: The North Country.

-

Date: Monday, July 16, 1990

Destination: Bodega Dunes S.B., Bodega Bay (C2)

Miles: 42

Total Climb/Descent: Up 2,685 / Down -2,722

High Point / Low Point: 436 feet / 0 feet

Feet Per Mile: 64

Route Score: 75 (Moderate)

-

The redwood trees of Samuel P. Taylor were gorgeous, and the campsite first rate, and when we pedaled out the next morning, we could sense we had entered a new stage of our journey.

For the past few days—really, since Monterey—we had been in built-up areas or less developed areas that were still linked to larger towns.

Traveling through San Francisco and Marin was exceptionally crowded.

But things on the northern coast would be different, and for the next 280 miles, the towns would be small, scenic, and built around tourism and logging (more on that later).

It was another cool and damp morning as we headed up through the tiny Point Reyes Station and along the narrow road flanking Tomales Bay.

The shoulder of the road was non-existent as it rolled over a never-ending series of short climbs and descents. The views were good, though, with the sheltered Tomales Bay giving off serious Scottish Loch vibes.

Still, it was nice to head inland a bit, where the gray coastal pall gave way to broken clouds with blue skies peeking out in places.

The road remained undulating, but now the farms spread across the rolling hills had an Irish countryside vibe. To the east, we knew the clouds gave way to blue skies and heat, and we were ready for some warmth, but that would have to wait.

As we headed back toward the ocean and Bodega Bay, the temps cooled and the skies grayed once again, giving the small town a distinct seaside-village vibe.

-

We had been bumping into Fred and Don for over a week now, sharing a campground hiker-biker site and then going a few days before linking up again.

Our pace was slow (about 10 mph before you factored in the breaks for food and sightseeing), so they usually went on ahead of us.

For the next five nights, however, we’d be sharing hiker-biker sites.

They were good guys, friendly and welcoming, and it was a pleasure to run into them.

In Bodega Bay, we also met Steve, a doctor from San Francisco who was heading to Glacier National Park, a trip of similar distance to ours. He was another nice guy we’d hang out with for the coming week. He rode a unique Bruce Gordon Rock n Road bike—arguably one of the first 700cc gravel bikes ever.

-

Day 9: Bodega Bay

A cold and dreary morning with small rollercoaster hills along the way. Snacked in Tomales. We had lunch and did laundry in Bodega Bay. We had dinner with Fred & Don at Scott’s Pizza. We also met Steve this night.

Day 10: A Good Test.

-

Date: Tuesday, July 17, 1990

Destination:Manchester State Park, Manchester (C2)

Miles: 69

Total Climb/Descent: Up 4,829 / Down -4,857

High Point / Low Point: 614 feet / 1 feet

Feet Per Mile: 70

Route Score: 221 (Very Difficult)

-

The ride from Bodega Bay to Manchester State Park was a long one. The Kirkendall book warned, “The ride … is long and demanding. The road is narrow, winding, and steep. Traffic is light, except on Summer weekends. The most serious hazard to cycling in this section is the sheep, who wander on and off the highway.”

This was both sobering and charming, and the promise of rolling, grassy hills, miles of wooden fences, surf-battered cliffs, small sheltered coves, and weathered sea stacks of all sizes and dimensions made us eager to get pedaling.

The route did not disappoint. Small villages dotted a rocky coastline. The mouth of the Russian River was picturesque (alas, no photos …).

North of Jenner, Highway 1 ran along a rugged, open coastline that felt wilder than anything south of it—a close cousin of Big Sur.

The road climbed onto broad, windswept headlands where the ocean spread out below in long, unbroken views.

Between the headlands, the highway dropped into small creek valleys bordered by low trees and weathered fences.

Soon, the land opened into rolling ranch country—simple fields, long fencelines, and a few scattered barns—before the route bent inland toward Manchester.

All of this made the ride, which was easily our hardest day yet, more fun than a chore—the memories are all good.

-

Forty miles into the day, we entered Sea Ranch, a small community of weathered gray wood homes with a modern, simple aesthetic.

Designed by a small group of Bay Area architects and designers in the early 1960s, the development was envisioned as a progressive, inclusive community, guided by the principles of good design and harmony with the natural environment.

The community stretched in dribs and drabs for seven miles along the lonely coast. Many of the houses looked to be vacant—or very secluded—and we joked that the whole area gave off serious “Witness Protection” vibes.

It was remote and a little creepy, but undeniably gorgeous.

-

Day 10: Manchester

The Russian River flowed through a beautiful valley before entering the ocean. We wanted to eat breakfast there in Jenner, but we had no such luck. We weren’t able to get food until Salt Point, 27 miles after we had started that morning. We stopped in Gualala for some yogurt, where we rejoined Fred, Don, and Steve. Food shopping in Point Arena, where we shared a campsite with the guys. No showers and pit toilets. Yuk. We walked to the beach, where there was a lot of driftwood.

Enjoying some afternoon sunshine while hanging with Don and Steve at the Manchester Campground. (Click image for geotag)

Don explains firepit basics to Fred (who is behind the camera). Manchester State Park. (click image for geotag)

Dinner with Steve and Fred. Manchester State Beach. (Click image for geotag)

After dinner beach exploring with the gang. Manchester State Beach. Note the indispensable and thoroughly awesome fanny pack that I rocked for the entire tour. (Click image for geotag)

Day 11: Redwood Summer.

-

Date: Wednesday, July 18, 1990

Destination: MacKerricher S.P., Cleone (C2)

Miles: 44

Total Climb/Descent: Up 3,221 / Down -3,227

High Point / Low Point: 436 feet / 1 feet

Feet Per Mile: 73

Route Score: 95 (Hard)

-

My brother turned me on to “The Monkey Wrench Gang” during our family trip to Alaska in the Summer of 1989.

Edward Abbey’s best-known work of fiction is a novel about the use of sabotage to protest environmentally damaging activities in the Desert Southwest. It was so influential that the term "monkeywrenching" has come to mean, besides sabotage and damage to machines, any sabotage, activism, law-making, or law-breaking to preserve wilderness, wild spaces, and ecosystems.

This was heady stuff for 23-year-old Sean, and I loved the book and all of Edward Abbey’s other works—especially Desert Solitaire.

That admiration continues to this day. Heck, the title of this website, “Take The Other,” comes from Abbey’s Road, one of his later books.

I’m not alone in my fondness for Abbey, and I’m not the only one who took his message to heart. The Monkey Wrench Gang inspired Dave Foreman to found Earth First! in 1980.

This environmental organization often advocated the sort of minor vandalism depicted in the book and had the motto "No compromise in defense of Mother Earth!”

In the summer of 1990, Earth First! organized a three-month environmental activism movement to protect old-growth redwood trees from logging by Northern California timber companies.

On this eleventh day of our tour, we entered the epicenter of that movement, which had been dubbed “Redwood Summer.”

While our arrival on the scene was happenstance, and we never really saw large protests or environmental actions, it did cause me to consider: What would I do if I knew, without a shadow of a doubt, that my actions would save a grove of old-growth redwoods?

Would I cross a busy highway? Of course. Would I walk five miles? Yep. Would I peacefully confront employees of the timber company? Err .. yes, but it’s no longer comfortable.

Would I lie down on a busy highway to stop traffic? To 100% save an old-growth grove? Probably.

Would I trespass and chain myself to a tree? Maybe. I didn’t know. I was glad I didn’t have to decide.

I did know that I didn’t feel comfortable destroying anything and would never intentionally do anything that could hurt somebody.

So, over the next week, I kept an eye peeled, wore my “Think globally, Act locally” T-shirt, and pondered how I could do the most good—but really didn’t do much at all.

Fortunately the success of Redwood Summer did not depend on my decisions, and it’s now considered a turning point in environmental activism.

-

So, my direct-action environmental activism fizzled, but that doesn’t mean I wasn’t directly affected by the North Coast timber industry during our tour.

Through Big Sur (and later along the coast just north of San Francisco), we had learned to ride on busy roads with little or no shoulders using a strange mixture of boldness and caution.

The trick was to read the traffic—and sometimes individual drivers—to determine when to pull over and when to take the lane safely.

In Big Sur, the traffic was mostly tourists. While they were often distracted and clueless, they were usually very considerate.

Many times, a driver would politely wait until it was safe to pass, giving us a thumbs-up or a friendly wave once they had moved past.

But on day 11, we had entered timber country, and the traffic now included the dreaded timber truck.

With the backdrop and tensions of Redwood Summer in mind, we took no chances, hugging the right margin of the road and pulling over and stopping when we heard one of the large semi-trucks approaching.

But this wasn’t always possible, and the first time a loaded logging truck blasted by us at 40 or 50 mph, it left a lasting psychic impression.

The drivers were professional and alert. They were also the apex predator on the road and had places to be.

We took the threat seriously and survived, but it was never routine when they passed.

-

Day 11: MacKerricher

Our first whole day of logging trucks.

We ate breakfast at a Cafe in Elk (a cute place with great music).

I went a little crazy on groceries that night. We just missed a beautiful sunset on the beach.

Steve and Don and a logging truck.

Day 12: Leggett Hill.

-

Date: Thursday, July 19, 1990

Destination: Standish Hickey S.R.A., Leggett (C3)

Miles: 44

Total Climb/Descent: Up 4,503 / Down -3,661

High Point / Low Point: 1,906 feet / 31 feet

Feet Per Mile: 104

Route Score: 131 (Difficult)

-

After almost two weeks along the damp, foggy coastline, we were heading inland today and into the heat.

The way was guarded, however, by the famous Leggett Hill.

Kirkendall and Spring had this to say in Bicycling The Pacific Coast: “A hill just south of Leggett is the principal point of interest for the section; with an elevation of nearly 2,000 feet, it is the highest point on the bike route. Cyclists talk about Leggett Hill up and down the coast, increasingly exaggerating its proportions as they go. Contrary to rumor, abandoned touring bags do not line the road, nor are there graves of cyclists who did not make it. Although a long climb, Leggett Hill is by no means the steepest climb on the coast.”

It was, however, a stout 9.3-mile climb that gained just over 2,000 feet. A “Cat 1” in Tour de France speak, but a lowly 1.97 using the more esoteric FIETS scale.

But it was to be a welcome change. We powered up with a big breakfast in Westport, in a room of an inn that looked very much like somebody’s dining room.

At mile 18, we turned inland and headed up through dense, shadowy forests. Again, the climb's consistency and honesty made it fun to tackle. We watched the miles tick off and chatted as a group.

Breaks in the canopy of trees revealed how much we had climbed—long vistas across deep forested canyon—and the rising temperature as we pulled away from the coast.

Finally, the climb eased, and after a strange three-quarters of a mile on almost perfectly flat road, we began our long plunge to the South Fork of the Eel River and Highway 101.

-

We descended into Leggett with temperatures well into the 90s and bright sunshine.

The tall groves of redwoods, however, made the heat bearable; more of a novelty with so much deep shade at hand.

We were in true redwood country now, nearly at the gateway to the famous Avenue of the Giants, and redwoods were the backbone of the tourist industry here.

Over the next few days, we’d be confronted with enticing tourist traps like the World Famous Tree House, Confusion Hill, and the Trees of Mystery (which featured an enormous 50-foot-tall concrete statue of Paul Bunyan and his ox Babe).

“Drive-through trees” were also popular. We had barely finished our long descent from Leggett before we were posing for a group photo at the “Drive Thru Tree of Park Leggett.”

(Alas, those photos were also lost in the rear pannier debacle of Day 37.)

But spirits and temperatures were high, and Standish Hickey campsite offered the first of many opportunities we’d relish over the next month: A swim in a river.

With a six-pack of beer and wonderfully tired legs, hanging onto a fallen log in the cold waters of the Eel River was precisely what we needed.

-

Day 12: Standish Hickey

The day we had been soooo worried about was here.

We had breakfast at a little inn in Westport. The lady was lovely enough to serve us some pancakes. The first hill wasn’t too bad, in fact, it was beautiful and peaceful with the trees, birds, river, and flowers—until you could hear the chainsaws in the distance.

Leggett was hard, but nothing impossible, and the downhill for the next two and a half days was great!

After making it down the hill, we decided to ride our bikes through the drive-thru tree.

On our way there, we ran into the guys who were having lunch. We ate and then went to the tree.

We got into camp, got a six-pack, and headed for the river! Ahh! It was great. We had dinner at the deli across from the campground, and I got eaten by mosquitoes.

Breakfast in Westport with Fred, Don and Steve.

The Leggett Chandelier tree with Steve, Fred and Don (click image for geotag).

Cooling off in the Eel River with Don and Steve after our climb over Leggett Hill. Cooling off in rivers when we had a chance would be a favorite pastime for the next month.

Day 13: Avenue of the Giants.

-

Date: Friday, July 20, 1990

Destination: Burlington Campground, Weott (C1)

Miles: 46

Total Climb/Descent: Up 2,821 / Down -3,541

High Point / Low Point: 925 feet / 171 feet

Feet Per Mile: 61

Route Score: 87 (Hard)

-

From Standish Hickey, we’d travel along Hwy 101, a major throughfare that picked up a lot of traffic.

Looking at a state map, you could see that this corridor was a bit of a choke point.

To the west was the near mythic Lost Coast, the most undeveloped and remote portion of the California coast, whose shoreline was deemed too rugged for state or even county roads.

To the east, there was the Klamath Range and a long, very convoluted four-hour drive before you hit the I-5.

So, no surprise: in some places, Highway 101 was a divided road with two lanes in each direction and felt like a freeway. It was a far cry from the roads we had grown accustomed to.

Fortunately, there were some well-timed side roads, like Hwy 271, that were far less busy and much prettier, with great views of the Eel River and many stands of tall redwood trees.

We had settled into touring life by now, and most riding and camping tasks were reflexive.

We had grown strong and resilient. Our many flat tires were no longer catastrophes. The true mark of competence was being able to patch a rear wheel puncture without removing the wheel from the frame.

But in some ways, we were still too goal-oriented and fixated on the route. We rarely made side trips and were hesitant to stop anywhere for too long. Once we got riding, we tended to keep riding, and most days, freewheeling spontaneity was frowned upon.

-

California 254, otherwise known as the Avenue of the Giants, parallels Highway 101 for 31 miles through some of the most scenic stands of coastal redwoods anywhere.

For us, it was an excellent opportunity to ride together as a group, often spreading out across the quiet road as it gently meandered down the Eel River Valley.

This was easy, scenic riding. The high temperatures were the only challenge.

Fortunately, we had reached Burlington Campground by early afternoon—when temperatures were peaking—and quickly were on the short trail down to the river for more, you guessed it, river swimming. A delight!

-

Day 13: Burlington

A relatively easy 47 miles, mostly downhill, but very hot! Upper 90s at least.

We met up with the guys in Garberville and had breakfast at the Eel River Cafe.

It was hot when we got back on the road, but the shade along the Avenue of the Giants helped.

We stayed at the regular campsite that night and went swimming in the river again.

It was Don and Fred’s last night with us, so we had a group dinner (in courses): corn, potatoes, steak, and chicken.

El Scorcho along the Avenue of the Giants.

Easy riding along the Avenue of the Giants

Ready for a swim as we near Burlington Campground in triple-digit temperatures. Avenue of the Giants

The Eel river swimming hole near Burlington Campground.

Day 14: Don & Fred’s Last Day

-

Date: Saturday, July 21, 1990

Destination: Patrick’s Point State Beach (C2)

Miles: 77

Total Climb/Descent: Up 3,076 / Down -3,091

High Point / Low Point: 391 feet / 5 feet

Feet Per Mile: 40

Route Score: 159 (Difficult)

-

The long ride to Patrick’s Point was memorable in several ways. It had the most mileage, a stout 77 miles, primarily through more developed areas near Eureka, the largest town since San Francisco.

It also marked our return to the foggy coast. The transition from the low 90s found along the Avenue of the Giants to the breezy 56 degrees that greeted us in Eureka was shocking.

Finally, it was Don & Fred’s last day, and we were sorry to see them go. Friendships on the road are easy to make and become surprisingly strong in a short time.

Don and Fred had been great to ride with—gentlemen and interesting. The road would be much lonelier without them.

Steve would be with us for a few more days, but then we’d part ways with him as well. He’d be heading up the Oregon coast before cutting east at Newport, riding to Northern Montana via Oregon State Route 26.

-

We’d be making dinner with Steve tonight. He’d be in charge of the pasta, and we’d make a salad.

So we stopped at “Saunders Trinidad Market” for lettuce, carrots, tomatoes, grapes, alfalfa sprouts, and bananas.

For dessert, I chose pie—but not just a slice, a whole pie.

We strapped the frozen French Silk Pie on my back rack, on top of our tent, and made our way to the campground.

I don’t think we ate half of it, but it made us laugh at the end of a long and chilly day.

-

Day 14: Patrick’s Point

Our longest day of the trip (mile wise) at 76 miles. We got off to a good start and didn’t stop for breakfast until Fortuna (the 30-mile mark), where we met up with the guys.

We hit some winds before breakfast and after Eureka.

Don & Fred waited for us at their freeway exit in Arcata to say “goodbye!”

We stopped in Trinidad to get food (only salad stuff—Steve got stuff for Spaghetti).

Patrick’s Point was beautiful but cold and foggy! Neat trail to the showers.

Dessert: Sean’s French Silk Pie.

Day 15: End of Stage One

-

Date: Sunday, July 22, 1990

Destination: Crescent City (American Best Motel) (H2)

Miles: 54

Total Climb/Descent: Up 3,891 / Down -4,082

High Point / Low Point: 1,236 feet / 10 feet

Feet Per Mile: 72

Route Score: 140 (Difficult)

-

We were slow on the draw at the beginning of this, our last day on the Pacific Coast.

For the past 693 miles, we had reveled in this spectacular part of the world: the cliffs of Big Sur, crossing the Golden Gate Bridge, the quaint towns like Mendocino, the grand sea stacks and rugged North Coast, riding through (sometimes literally!) redwoods.

It had been spectacular. But we had drunk our fill, and I think we were ready for something new—or at least something a bit warmer.

Dawn arrived at Patrick’s Point Campground with foggy, drippy conditions and a morale-sapping temperature of 54 degrees.

For the past two weeks, we had camped out every night except one. Our tent was soggy, and we were worn out. Physically, we were doing okay, but mentally, we were ready for a break, a bed, pillows, and a toilet you didn’t need a flashlight to find.

Fortunately, our first Zero Day was approaching—all we had to do was get there.

We had said our goodbyes to Steve, who left slightly before us. We might see him along the road, but there was a good chance we wouldn’t.

We freewheeled down the small hill to Big Lagoon, where we met a slight but noticeable headwind and fog so dense we thought it was raining.

Pedaling around this lagoon and Stone Lagoon after it, we felt cold and tired and lonely—also a bit trepidatious about the days to come, when we’d leave the well-worn bicycle touring groove of the Pacific Coast for the lesser-known challenges of the Cascades.

We warmed up in Orick at a very mediocre breakfast spot, and the fog lifted a bit, but our mood was poor as we started up the first of two significant climbs standing between us and day’s end.

As our muscles warmed, we appreciated the gentle grade up into Redwood National Park, but the climb through Del Norte Coast Redwoods State Park nearly broke us. I could see that Christy was really struggling. So was I.

-

The steep, 1,000-foot descent into Crescent City was so welcome, and we decided then and there that we had reached the end of the road for the day.

We pulled into one of the first motels we encountered (American Best Motel) and paid the $62 for a room without a second thought.

The harbor was across the road, and downtown was nearby, but we were content to cocoon, take long hot showers, and watch TV. When dinner time arrived, we didn’t even venture out of our room, opting instead for pizza delivery.

The pizza was lousy, but we were content. The next day, we’d leave the coast for good and start a new stage of our adventure.

-

Day 15: Crescent City

Our last full day on the coast. I was in poor spirits, to say the least, and tired from the day before.

The day began with such heavy fog that we thought it was raining.

We got a late start and stopped for breakfast in Orick (a Podunk town).

I was having a terrible day, so Sean convinced me to get a motel in Crescent City. We found a nice place and ordered a pretty bad Pizza! But it was great to sleep in a bed.

Part Two: The Cascades

Day 16: Six Small Steps

-

Date: Monday, July 23, 1990

Destination: O’Brien and Scotty’s House (Home Stay)

Miles: 46

Total Climb/Descent: Up 3,700 / Down -2,295

High Point / Low Point: 2,153 feet / 15 feet

Feet Per Mile: 81

Route Score: 113 (Hard)

-

Spirits were much improved this morning. Some creature comforts, some TV watching, and a long sleep in a bed had us ready to tackle a new chapter in our journey.

Of course, when we wheeled our bikes out of our room, we saw more gray skies.

This time, however, we were sure they would not last.

Less than a quarter mile north, we made a turn on Elk Valley Road and left the Kirkendall book behind for good. From now on, the route would be mine.

The road was lined with residential homes and small farms, and it was very quiet and peaceful. The first few miles were going great.

That did not last. Turning onto Hwy 199, the route we’d follow all day, we saw the first signs: “Bridge Out. Road Closed Ahead” and then some instructions on the appropriate detour.

We looked at our state map, and our hearts sank. The detour looked like it would add somewhere between ten and twenty miles to our day—it was hard to tell—and would take us back to the soggy coast.

We were just three miles from the bridge. Was it worth our while to see if it was actually closed? Maybe two bicycles could get through.

We hemmed and hawed for a few minutes and then rolled the dice. No detour for us before we at least knew it was impossible to make it through.

Christy wasn’t completely sold and seemed exasperated by the whole situation, but was willing to try.

We climbed up a short hill through another redwood grove (“more damn redwoods!”) and then coasted downhill to the Smith River.

More signs and a large fence greeted us, but we also saw something else. While the main overpass was indeed a long way—months and months—from completion, there was a smaller, slightly dicey-looking temporary construction bridge just to the north.

You would not want an RV crossing it, but it looked just fine for a couple of bicycles.

We saw a construction worker and told him our story, trying to look pitiful and pleading—which was not hard to do.

He said it was no problem for us to take the construction bridge, but there were “six steps on the other side” we’d have to figure out how to get over.

Six steps to save twenty miles? Heck, yeah! We were saved. We rode over the temporary bridge, feeling oh-so-smart, and then got our first look at the steps.

Except they were not steps. The hillside on the far side of the river had been graded, and there were a series of terraces, each six feet tall, that led up to the nearby road, where we could occasionally hear a car pass.

I counted the terraces. There were six of them.

Well, a job started is a job half finished. I clambered up my frame so I could belly crawl onto the first flat. Then, with Christy pushing and me pulling, we heaved our 70-pound bikes onto the platform.

A hand down helped Christy climb up.

Now repeat five more times.

Fortunately, our technique improved, and the steps lost a bit of height near the top.

We pulled out onto the highway dirty and sweaty, but with huge grins on our faces. Less than an hour had passed since we saw the first road-closure sign.

-

For the next 30 miles, we slowly gained altitude as we followed the Smith River to the Northeast.

We stopped for breakfast at the historic Hiouchi Cafe (“Best breakfast in the county!”) and continued to follow Greg Lemond’s progress in the Tour De France, where he had a good chance of repeating his victory.

Soon, the sun burned off the morning fog, and the temperature rose to the low 70s. Wonderful!

The Middle Fork Gorge of the Smith River was spectacular, the water an emerald green as it cascaded from one deep, rocky pool to another. Traffic was minimal, and the climb was gradual.

We continued up the river, passing small villages and campgrounds. As the sun rose, the heat slowly ratcheted up and traffic increased, but the riding was still good.

What a relief! This was the first day on routes that I had designed myself, and I was never sure what the roads would be like until we actually encountered them in person.

The riding felt remote after the wonderfully named hamlet of Darlingtonia. While towns were few, there were bathrooms in the many campgrounds we passed, which kept things civilized.

We passed the Patrick Creek Historic Lodge at mile 26, but kept on climbing. There were logging trucks, but also many turnouts where we could look down to the river.

We stopped at the palatial Collier Tunnel Rest Area before heading through its namesake tunnel (short and not very scary).

Suddenly, the road pointed downhill, and we zoomed down to the Oregon border and the adventure of the Cascades beyond.

We had done it! Our first day on our own, on our own route, and it had been a good one.

Even the six steps seemed like a happy anecdote.

-

This, sadly, is Christy’s last journal entry from the road.

Day 16: O’Brien

Our first day in uncharted territory.

Only a couple of miles in, we got to the 199 and saw a sign reading "road closed to through traffic."

The detour was 25 miles out of our way, so we decided to risk it.

When we got to the end of the road, there was a ½ build bridge! Great!

One of the construction guys said we could take the construction bridge and then push our bikes up the steps on the other side.

No Problem! Until we got to the steps. They were six feet high.

Day 17: Zero Day

-

All hail the mighty zero day!

Date: Tuesday, July 24, 1990

Location: O’Brien, Oregon (Home Stay)

Miles: 0

Total Climb/Descent: Up 0 / Down -0

High Point / Low Point: N/A

Feet Per Mile: N/A

Route Score: N/A

-

After sixteen straight days, where we racked up 793 miles and 48,856 feet of climbing, we finally had a day off at Christy’s uncle’s house near O’Brien, Oregon.

She had warned me that they were a little “Hippy Dippy,” but they were also very welcoming and kind.

Rick Butts and his second wife lived on what I’d consider to be a farm—it had chickens at least. At the minimum, it was country living unlike that available in San Diego and Orange County.

They had a young toddler, and Rick’s wife dropped the front of her dress so she could breastfeed while we were sitting at the table with them—something that seemed like it was from another planet back in 1990.

-

Our stay in O’Brien was restful and productive.

We slept in, did laundry, and hung out with Scotty, Rick’s first child, who was a few years younger than Christy.

We were also able to address some bike maintenance issues.

A distinct popping noise had developed in Christy’s front hub, and it only seemed to be getting worse. So Rick loaded the bike into his truck and drove us down to Dick’s Bicycles in Grants Pass.

Zooming down the road at 60 miles per hour was thrilling—how soon we forget just how fast you can go in a car!

The bike mechanic said the race on Christy’s front hub was blown, with the ball bearings beginning to shear apart because of it.

Christy recalled that he recommended a new race, but I opted only for new ball bearings.

It sounds pig-headed and short-sighted, so it’s probably true—but I have no recollection of it.

Anyway, with new ball bearings in the hub and some spares to take with us, we were ready to be back on the road.

The route ahead: After climbing over the Klamath Range northeast of Crescent City, we'd hit the sunny valleys of southern Oregon. After a rest day in O'Brien, we camp on the Rogue River before tackling a long, two-day climb up to Crater Lake. From the national park we'd head offroad over Windigo Butte, and spend a few days on the Cascade Scenic byway into Bend. It all sounded good on paper. Reality, however, was a bit different.

Day 18: The Rogue River

-

Date: Wednesday, July 25, 1990

Destination: Valley of the Rogue S.P., Rogue River (C3)

Miles: 49

Total Climb/Descent: Up 1,591 / Down -1,989

High Point / Low Point: 1,674 feet / 904 feet

Feet Per Mile: 32

Route Score: 52 (Moderate)

-

It had been less than three weeks since we left home, but the experiences of those 18 days had built a wall in our brains, a clear line between “before” and “now.”

Seldom do you have an opportunity to file away so many memories in such a short time. We knew we were in the midst of something special, something that was rewiring our brains.

A big part of that was the mode of travel itself. Each day was undeniably real. We could stick our foot down at any time and touch the ground. We were actually there.

Geography lost its abstraction: each climb, each descent, each gust of wind had a physical consequence.

We were no longer passive observers. We couldn’t be. We were experiencing the topography, the geography, in a way that’s never possible while riding in a car.

Climbs made us sweat; fast descents chilled us and made our eyes water. We felt the wind, smelled the sea air and roadkill. We could feel the energy a meal gave us. We were fully awake.

And so the memories piled up fast, and the days seemed to elongate, until it seemed impossible that so much had occurred in such a short period of time.

Time had become malleable.

We laughed about it, talked about it. It was amazing.

Twenty-five years later, we stumbled upon someone experiencing the same thing.

“I think that's what travel in general does: it wakes up your brain,” says traveler and author Jedidiah Jenkins. “I'll go into a new country, from Panama to Colombia, these countries I'm, like, scared of because of the news—and I'll find it beautiful and shocking.

“Every hill I cross over is insanely awesome. My brain is fascinated. I didn't know my brain could be so turned on.”

“I want to be aware of every day I'm alive, and I want to make it to 85 and be exhausted because I have been alive and awake every single day.”

“When you're a kid, everything's new, so you don't have to work for it—you're just astonished. Once you're an adult, that's a choice. You choose adventure for your own life. But it's not about the bike; it's about getting out of your routine and that could look like anything.”

“That's what I'm doing here. That's why I'm doing this bike trip, because I don't want my days to control me. I don't want my life, the calendar, to be my boss. I want to control my days. I want to choose the adventures that I go on. And I want to choose a mind and a soul that's wide awake, because in a sense it turns your hundred years on this planet into a thousand.”

-

We said goodbye to the Butts family and were on the road by 9:30 a.m., heading north on Highway 199 toward Grants Pass and the Rogue River beyond.

It looked like a straightforward route, following the Illinois River, before gradually climbing up to Hayes Hill Summit. From there, it would be a steep descent down into Grants Pass, a town of 17,000.

Traffic was heavier than we had seen in a while and the roads were much straighter, so cars were whizzing by us. The shoulder was wide, however. The only new treat Oregon had for us was the placement of rumble strips on the shoulder. These were deep enough to rattle the fillings out of our teeth if we strayed into them.

The road also had a different vibe. We had flipped the switch from sightseeing, scenic roads, to roads designed to get you from point A to point B. Transportation-first highways.

We were also now on roads that didn’t see many bicycle tourists, which made us minor novelties whenever we stopped.

“Where are you going? Where did you come from? You know there are mountains ahead, right?” It was fun being the weirdos, but we missed the camaraderie of the coast and looked in vain for other bikepackers for the next three weeks.

We reached Grants Pass (“It’s The Climate!”) in the early afternoon, with temps nudging into the middle 80s, which felt pretty good. We also knew that a swim in the Rogue River awaited us at the campground.

We pulled into a lunch spot and rifled through the old sports pages. There it was: Greg Lemond had secured his second Tour de France victory right about the same time we were lugging our bikes over those six small steps.

We enjoyed following the race and were grateful to read this final report. Coverage in newspapers was sporadic. With the internet still years away, who knows when we would have learned of his victory otherwise.

We began to follow the Rogue River upstream at mile 37. We’d be following it for the next two days as we climbed into Umpqua National Forest toward Crater Lake National Park. The river’s gradient was mild here, however, and the pedaling was easy.

The campground was large and busy, but it lacked a hiker/biker campsite. It also lacked an established swimming area. The river looked broad and powerful—much larger than the Eel River. With temps in the low 90s, however, we still cooled off as best we could.

It was strange—and a bit lonely—not to be in a hiker/biker spot, however. But the showers and firewood made up for it, and we had a peaceful night along the river.

Day 19: Farewell Bend

-

Date: Thursday, July 26, 1990

Destination: Farewell Bend Campground (C1)

Miles: 63

Total Climb/Descent: Up 3,534 / Down -1,145

High Point / Low Point: 3,413 feet / 1,017 feet

Feet Per Mile: 56

Route Score: 149 (Difficult)

-

We woke up to another clear, dry morning, with cool temperatures we knew wouldn’t last.

It was going to be in the mid-90s today, so we were eager to make an early start and gain some altitude—and forested shade—before the afternoon hammer descended.

We stopped for breakfast in Gold Hill, poring over our Auto Club Oregon state map as we ate French toast, ham, and hash browns.

The route looked straightforward: 15 miles on Highway 234 before about 40 miles of gradual climbing into the Cascades on Highway 62, to the doorstep of Crater Lake National Park.

After breakfast, it was still a cool 70 degrees as we slowly followed the Rogue River north. The road was forested and offered only glimpses of the Rogue, but we could hear Dillon Falls as we rode past.

We left the river and entered farm and ranch lands, with many large homes on either side of the road. It looked fertile and prosperous.

Tall, wooded hills were all around us, but the wide valley carved by the river kept the gradual climb barely perceptible. The local traffic—mostly pickups—was courteous.

At mile 20, we crossed the river again (something we’d do four more times that day) and saw our junction with Highway 62 ahead. Gulp! The road had a lot more traffic, including semi-trucks, but the shoulder was wide enough.

We had climbed about 800 feet in the first 20 miles but had 2,800 still to climb. Now, the road tilted up. Straight ahead to the north, we could see the blue-green silhouettes of forested mountains.

We had reached the High Cascades.

-

We passed Shady Cove, a small town with markets, river rafting guides, and small motels—a holiday sort of place. The river was close to the road, which offered good views.

We could see small rafts floating on the current and fishermen on the riverbanks. We had crossed some invisible threshold into a more forested land.

At mile 30, the road made an abrupt turn east, and the hills began to crowd around. The shoulders narrowed, and the sun on my neck felt hot.

We crossed over the river again at the base of a long, steep hill. This one wasn’t fooling around, cutting through the basalt folds of the mountain in a straight line up.

We climbed the 6% grade for two miles to Lost Creek Lake. The road, having broken free of the timid gradients of the lower valleys, now climbed steadily into the mountains before us.

We were winded, hot, and sweaty—our water bottles nearly empty—as we crossed over the lake on Peyton Bridge and rode up to the small village of Prospect.

Now the change in scenery was unmistakable. We entered a forest of tall Douglas fir and ponderosa pines. The straight road split the forest canopy like a Death Star trench. The hot temperatures moderated, campgrounds began to appear to our right and left, and the speed of the passing cars eased.

Just like that, it was suddenly scenic.

But it had been a long, tiring day with very little coasting and many miles of gradual climbing—we were fried, and the road did not relent now.

The afternoon sunshine slanted through the canopy as we rode past the 59-mile mark (our expected finish line), but there was no end in sight.

Three miles later, we reached Union Creek Resort with its picturesque lodge, tiny market, and small cabins.

We stocked up our supplies and heard good news: our campground was only a mile ahead.

Farewell Bend Campground felt remote and quiet. The tall trees murmured in the breeze, and the river lazed past our campsite. The Rogue had been our companion all day, but here we would part ways. Tomorrow would be a long, non-stop climb up to Crater Lake.

Recent Google Map images of Highway 62 and Union Creek Resort.

Day 20: Burning Sensations

-

Date: Friday, July 27, 1990

Destination: Mazama C.G., Crater Lake National Park (C3)

Miles: 32

Total Climb/Descent: Up 3,969 / Down -1,357

High Point / Low Point: 7,122 feet / 3,408 feet

Feet Per Mile: 126

Route Score: 84 (Hard)

-

Today’s ride would be part novelty, part drudgery. At 19 miles, it was the shortest day of the entire tour. A lark. A jaunt. But those 19 miles were all uphill, a "hors categorie" climb to Crater Lake’s Mazama campground. This was more sobering. The topo map showed a long procession of contour lines we’d need to surmount as we climbed the dormant volcano.

From Farwell Bend, it was less than a mile until the road split, and we turned toward the mountain, still hidden by the dense forest. The grade was modest, but unrelenting, climbing about 1,000 feet every five miles. We labored in silence, sweating in the cool morning air, maintaining a pace of about 6 miles per hour.

After an hour, we passed the Thousand Spring Sno Park, and the views opened up. My daydreaming kept my mind occupied as my body tackled the task at hand. I drifted from thought to thought until a line of verse reared like an iceberg:

A nice breeze blows in

Whenever the big fella cracks a grin

And when the time and the place is right

We sit down, sip some bouillabaisse.Ah, you know I'm gonna have me a little fun

I got a candle, I can get a lot of reading doneThen my voice booms out in the overly quiet morning:

“Somewhere the sun is shining

On this world, but not for me

Two lovers' hearts a-rising

Oh, how long before I'm free?”I cackle and then pant from vocal exertion, and I hear Christy pick up the tune from behind me.

“I feel like Jonah in the belly of the whale

I get so lonely in the belly of the whale(Oh, oh, oh-oh-oh-oh)

Yeah, I feel like Jonah in the belly of the whale

(Oh, oh, oh-oh-oh-oh)”Our Burning Sensations' “Belly of the Whale” karaoke continued, and the miles slipped by. We felt good, the sun was shining, our bodies were strong, and we made a good team. It was just about perfect. Even a 19-mile climb couldn’t bring us down.

-

“Well, this is unexpected,” I thought.

Mazama Campground was hot and sun-baked, nearly empty in the noon sun. Everyone seemed to be at the lake, another 1,200 feet above us.

We unloaded our bikes and set up the tent, unstuffed our sleeping bags, and inflated our Therm-a-Rests.

“Now what?” I wondered. The campground was luxurious: showers, laundry, a store, and a restaurant. It would not, however, provide six hours of entertainment. We waffled for a bit, then did the only logical thing: hopped back on our bikes and headed uphill.

Stripped of our panniers and luggage, the bikes felt squirrelly but seemed to surge ahead with every pedal stroke. We were already warmed up and tackled the grades with gusto. A truck passed us, slowed down, and asked if we wanted a lift to the top. We declined and waved thanks.

I shifted down to a bigger gear and got out of the saddle, slowing my cadence to a waltz as I moved up through the switchbacks near the rim.

“Oh, what a beautiful morning

Oh, what a beautiful day.

I’ve got a beautiful feeling,

Everything’s going my way.”I sang with the requisite irony, distilling out the saccharine for a thin veneer of toughness, a world-weary indifference. Who was I kidding? It was gorgeous, and the ability to ride up 4,000 feet with such moderate effort was exhilarating. I’d remember this feeling 24 hours later and wonder how it could be the same person.

But for now, it was all good. We crested the climb and rolled along the rim, gawking at the deep blue lake 1,000 feet below, an impossibly gorgeous setup under perfect blue skies.

We locked our bikes outside the Crater Lake Lodge, a historic hotel built in 1915 that embodies the National Park Service’s architectural style—heavy log work, broad porches, and big stone chimneys. Inside, expansive windows faced the caldera, offering views that have wowed generations of visitors.

I had seen photos, nodded in appreciation at the aptly named Wizard Island, but seeing it in person was staggering.

We lingered on the rim, taking photos we’d never see, listening to the stillness of this grand space, enjoying the satisfaction of being here—soaking it all in. It had been a great day, one of the best, capped by a zooming descent back to our campground in the late afternoon.

We were bulletproof, I thought. Nothing could stop us.

If only. Our humbling was near, and it wouldn’t be kind.

Day 21: Windigo Butte

-

Date: Satuday, July 28, 1990

Destination: Spring Campground, Crescent Lake

Miles: 73.8

Total Climb/Descent: Up 5,377 / Down -6,533

High Point / Low Point: 7,678 feet / 4,221 feet

Feet Per Mile: 74

Route Score: 303 (Extremely Difficult)

-

The sun had turned the tent into a cozy Easy-Bake Oven as we contemplated getting up and moving at Crater Lake’s Mazama Campground. Our legs felt tired and heavy after all the climbing we’d done the past two days. More of that was on tap today, too.

But it was going to be an interesting and scenic route: we’d climb back up to the rim of Crater Lake again this morning before beginning a long descent off the volcano, through forests and pumice fields to a dirt forest road that climbed up and over the ominously named Windigo Butte.